“Ahrensfelder Obstwiesen” – Urban Periphery and Housing

“Berlin or Brandenburg – for those who can’t decide.“This is how project developer Bonava advertises its new residential development Ahrensfelder Obstwiesen at the northern edge of Ahrensfelde’s town center, where single-family homes, semi-detached houses, and row houses are being built as privately owned residences.

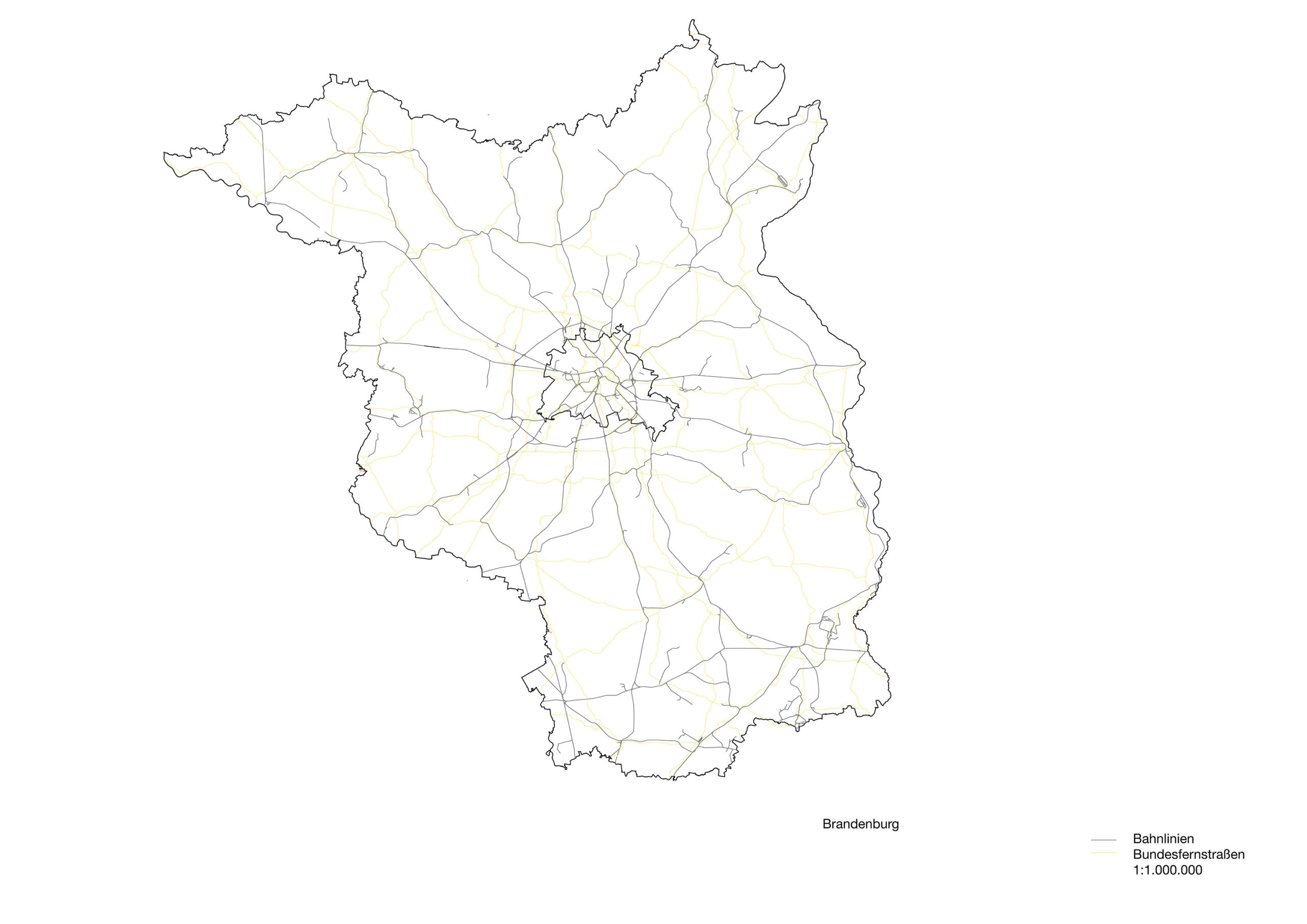

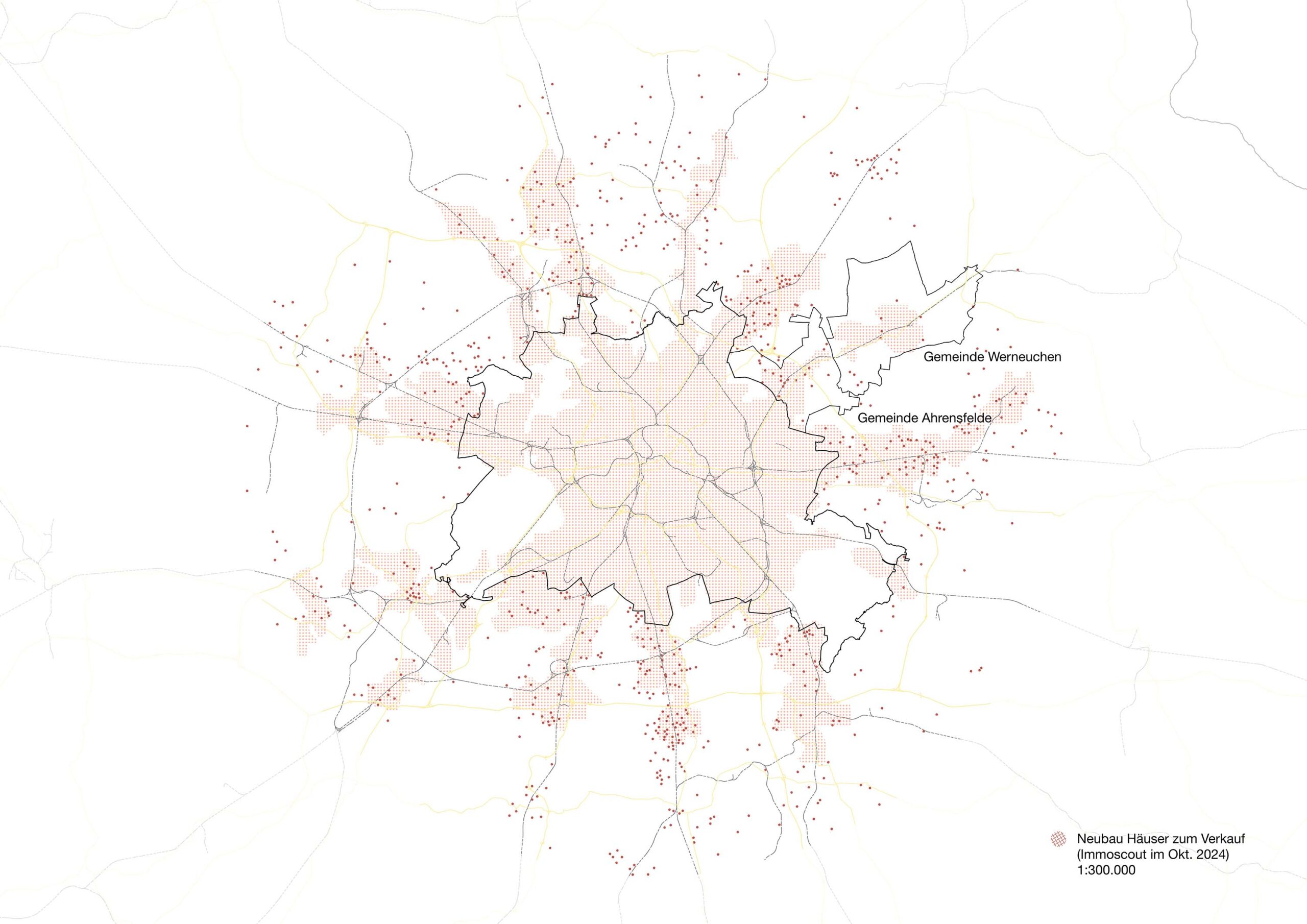

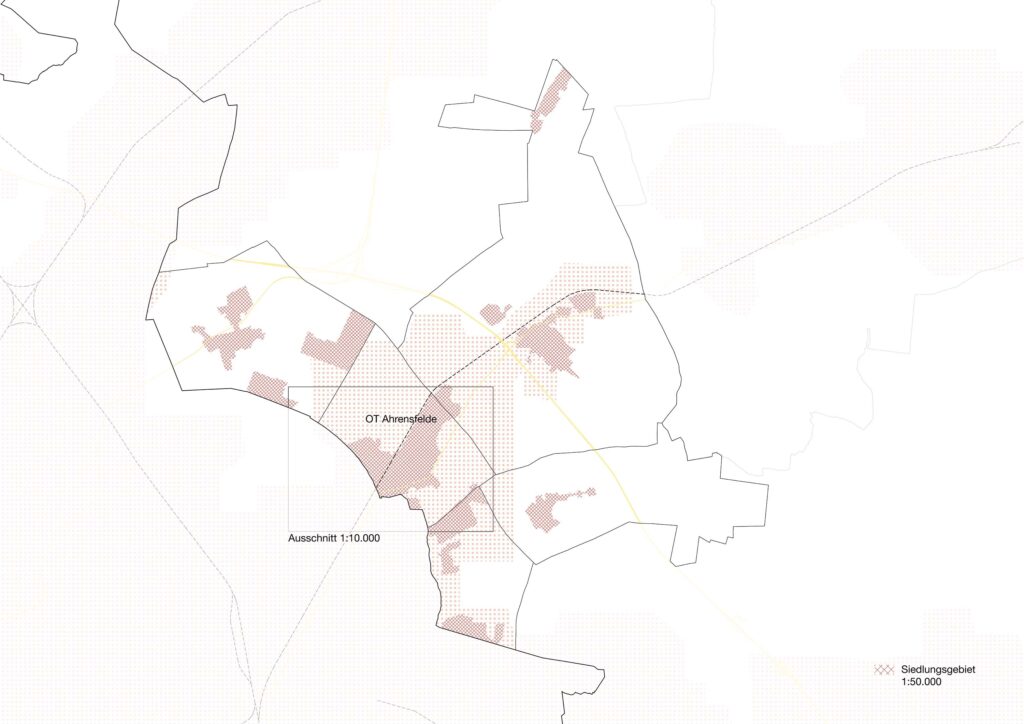

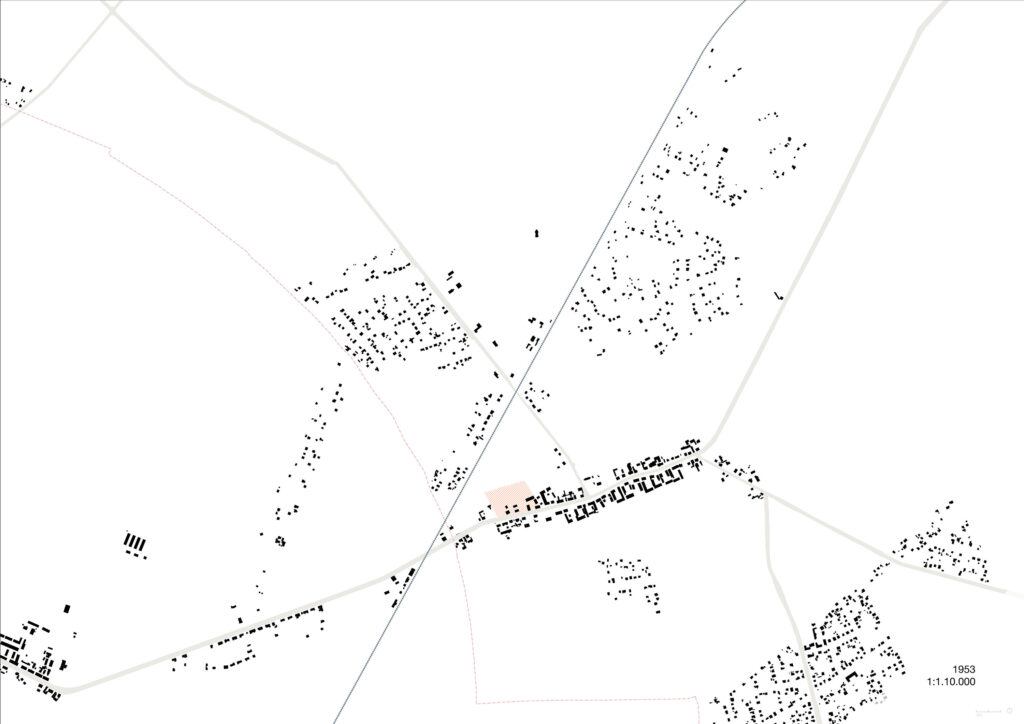

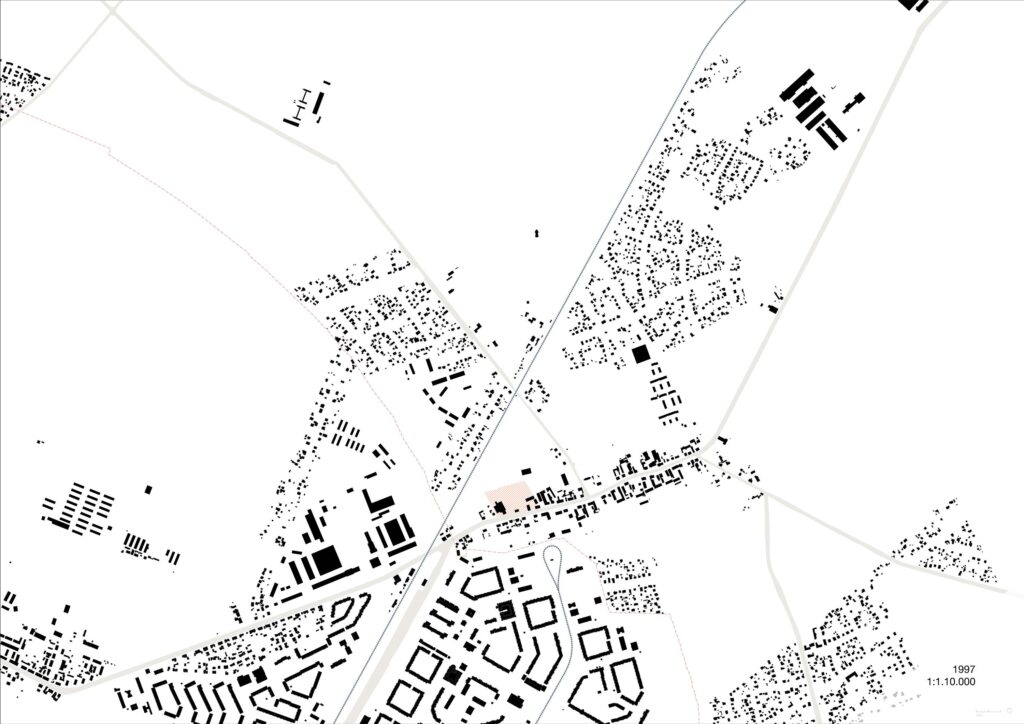

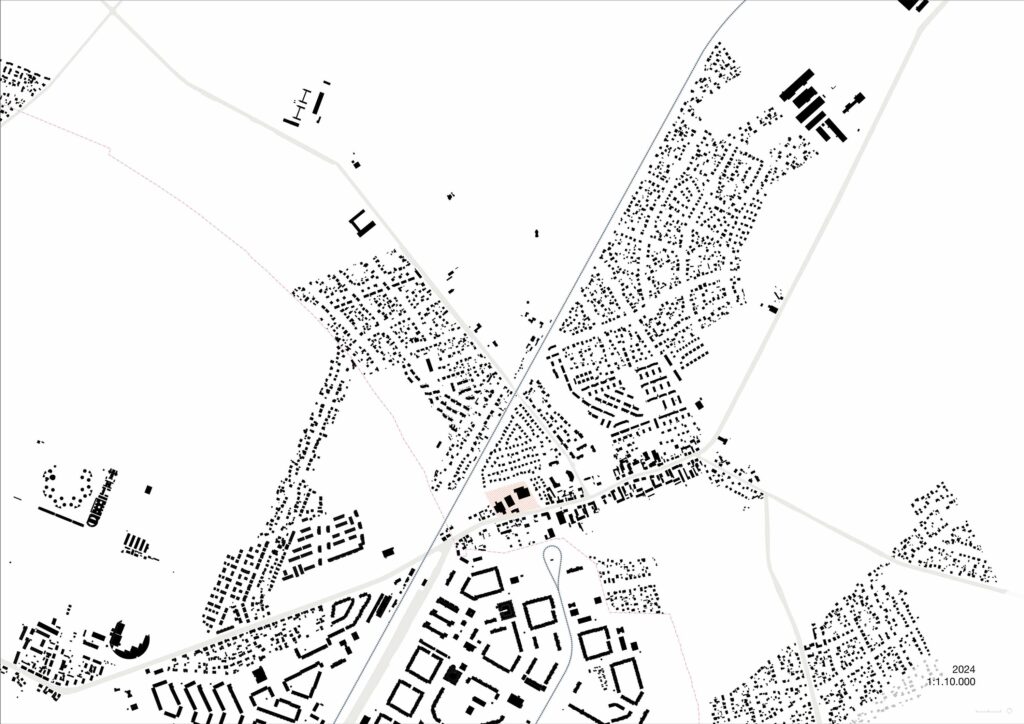

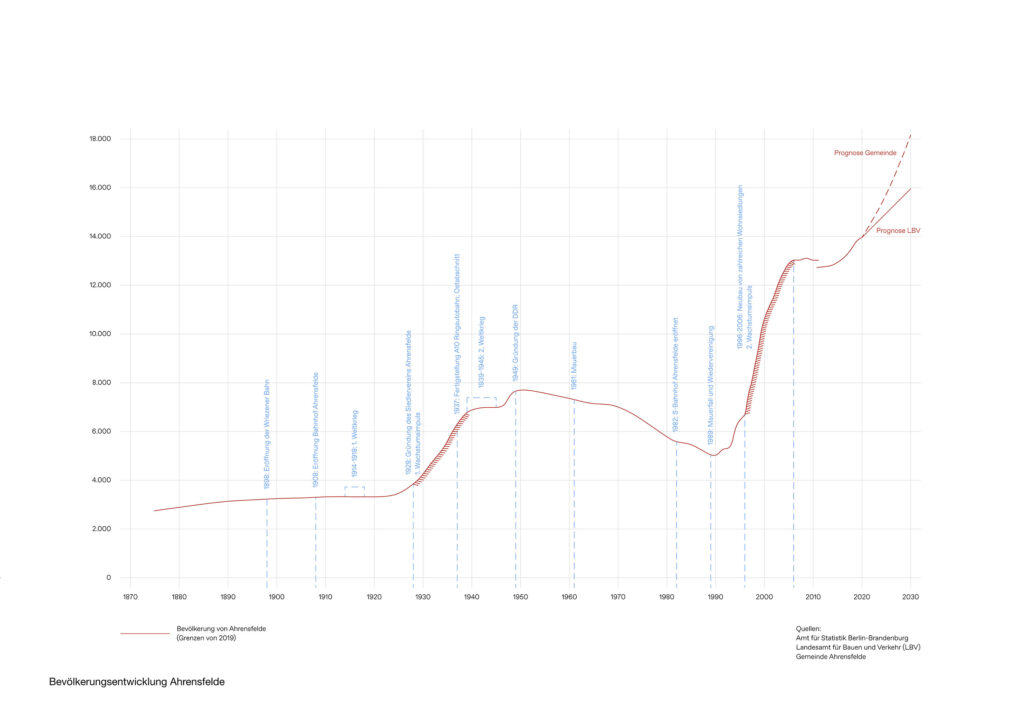

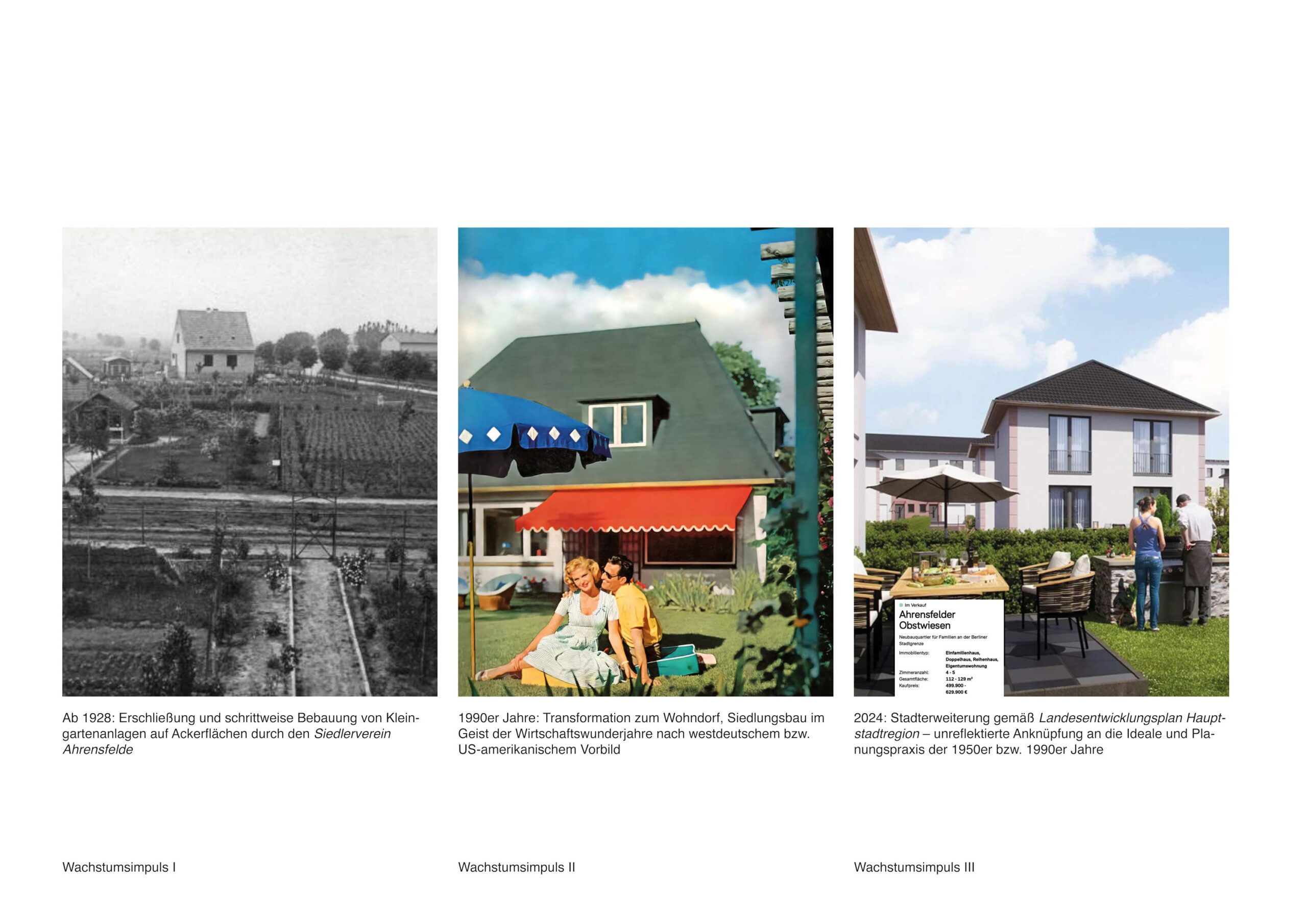

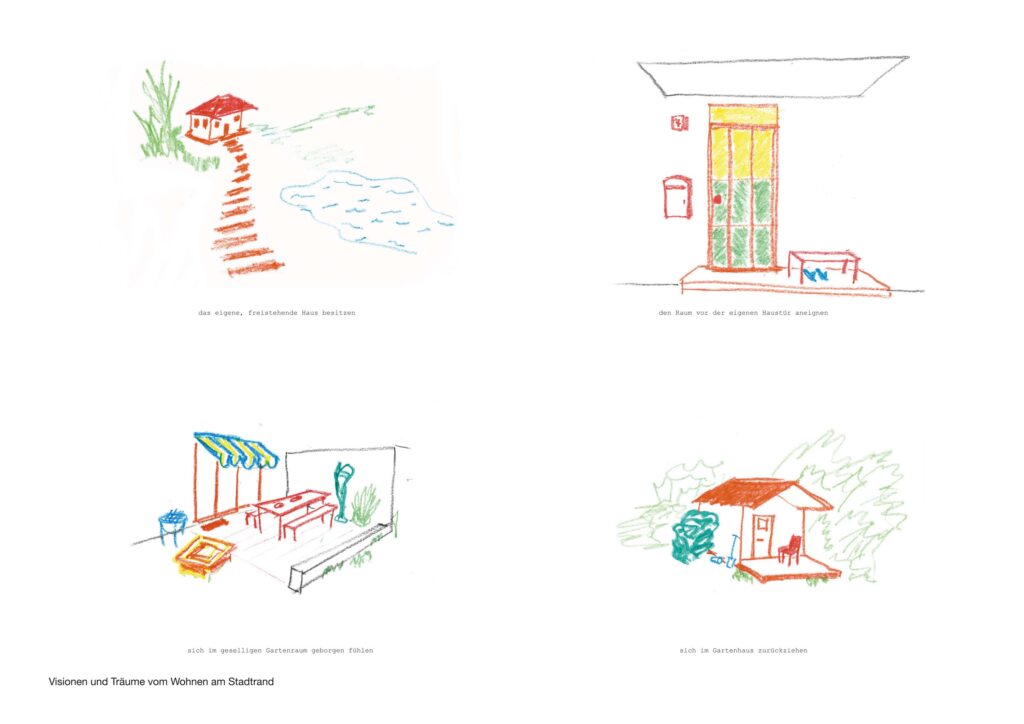

Berlin is growing and Ahrensfelde–Werneuchen is one of the development corridors identified in the so called Capital Region Development Plan (Landesentwicklungsplan Hauptstadtregion). Massive construction is taking place on the periphery, often outside of public discourse. Ahrensfelde, once a linear village, is expected to experience another wave of growth. But what might a more meaningful urban expansion look like here? And does the urban periphery hold specific spatial qualities that can be reflected in residential floor plans?

Homogeneity

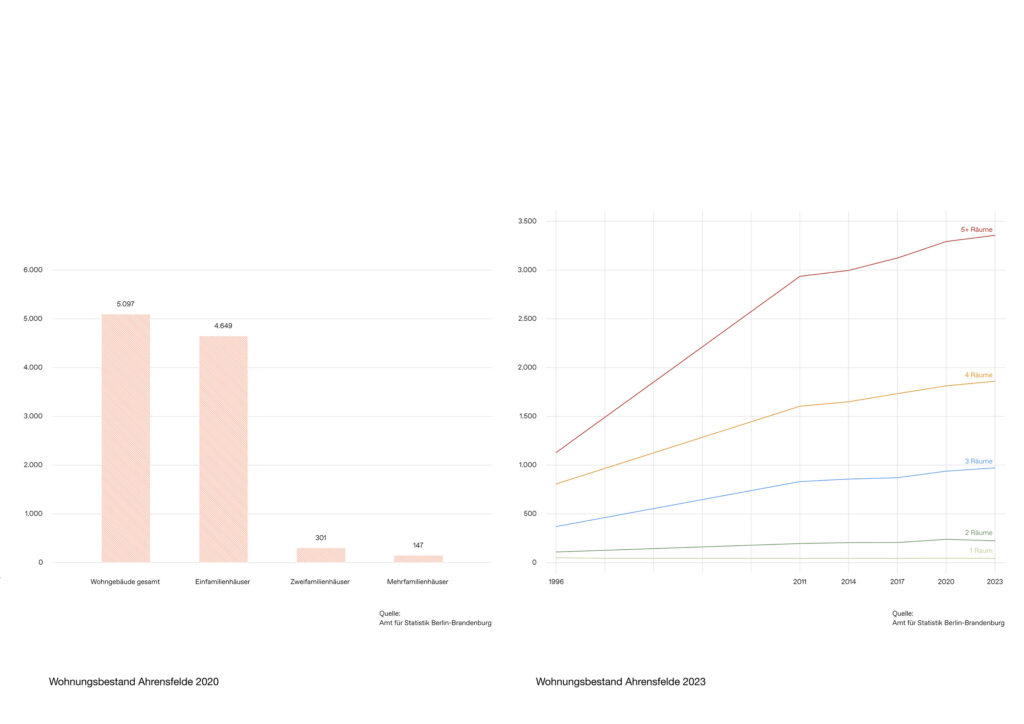

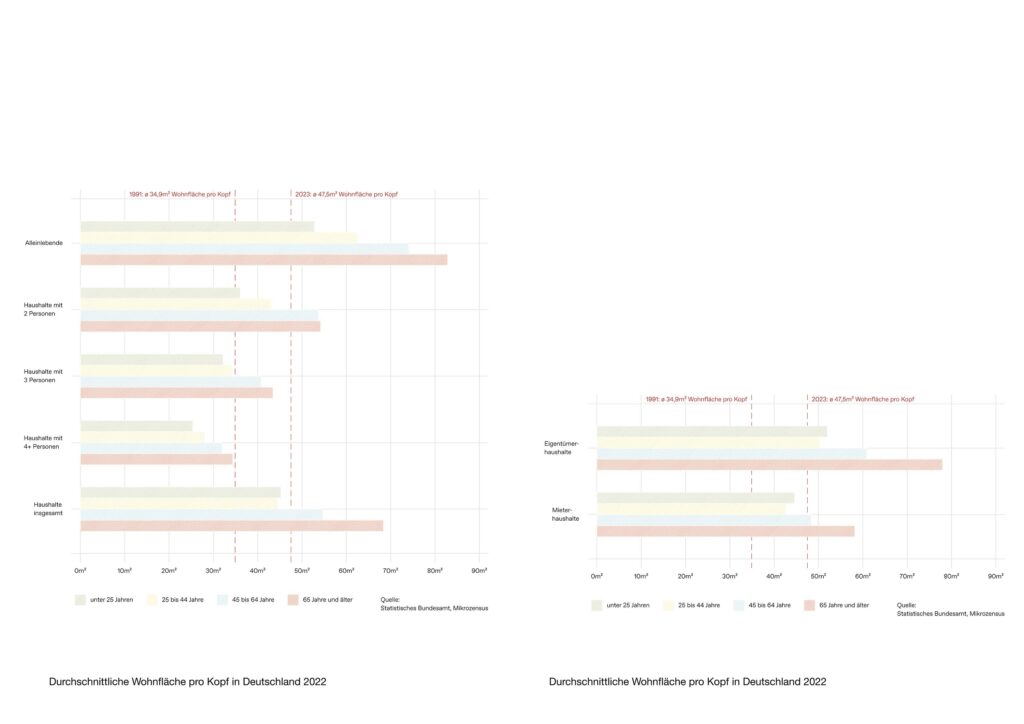

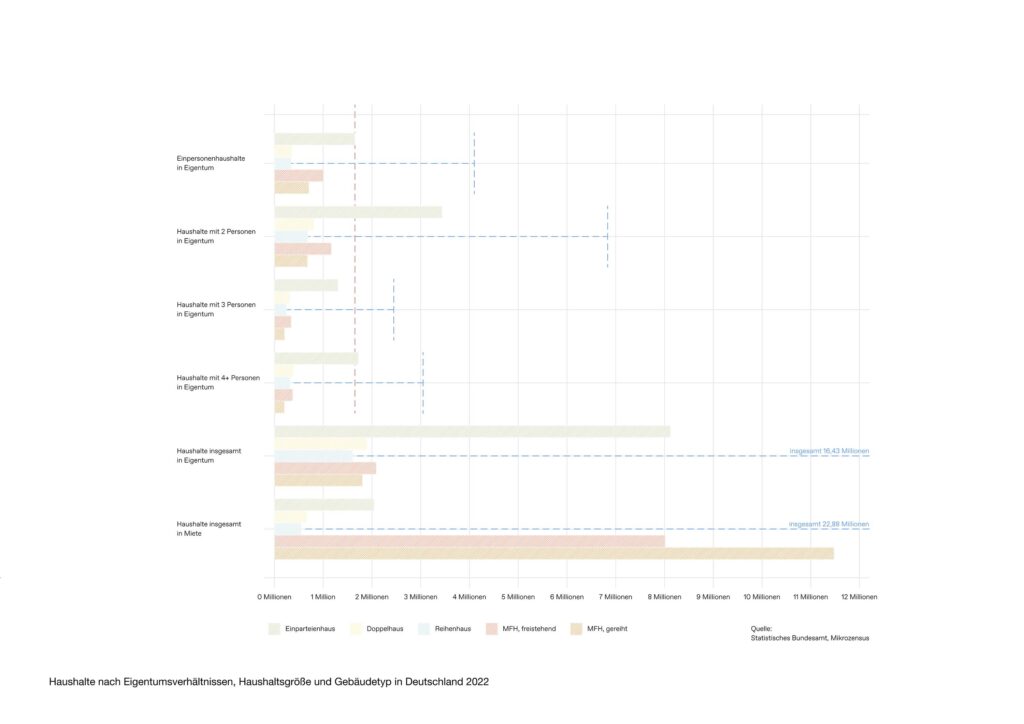

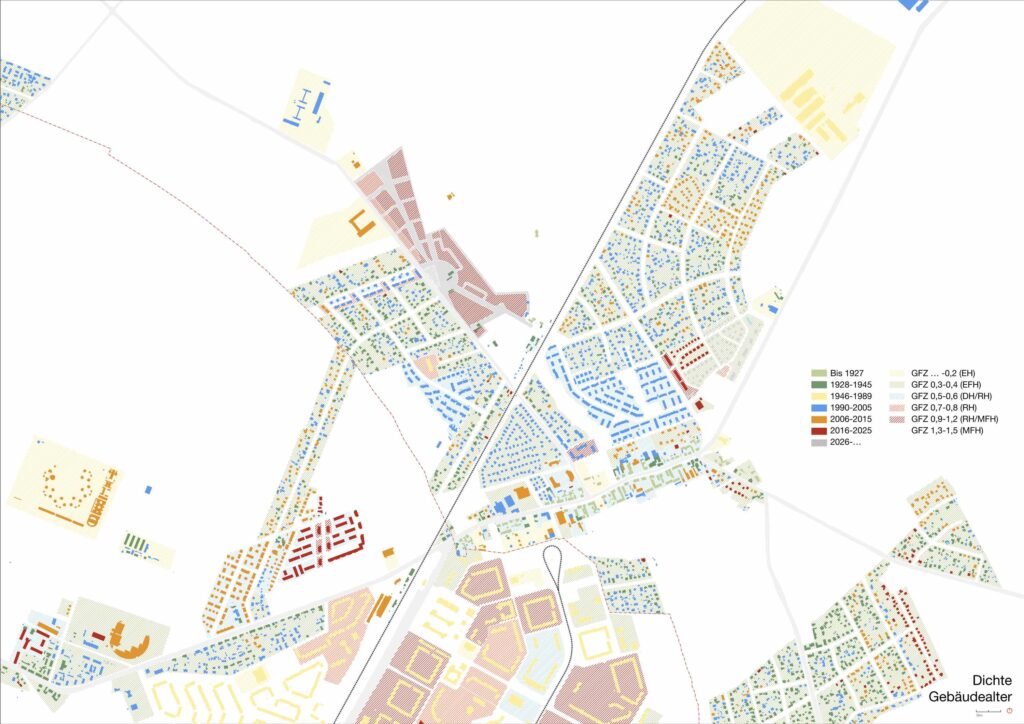

Ahrensfelde’s previous growth phases (1930s, 1990s) were closely linked to the dream of owning a family home with a garden. Today, more than 91% of the housing stock consists of single-family homes with five or more rooms. Other demographics find little to no suitable housing, and there are few alternatives that allow people to adapt their living situation to changes in their life course.

What is needed is a more diverse housing offering and an increased density—architecturally, programmatically, and spatially. Only through this, and by clearly differentiating itself from city and village, can the potential of the urban periphery be strengthened and made accessible to more people.

Public space

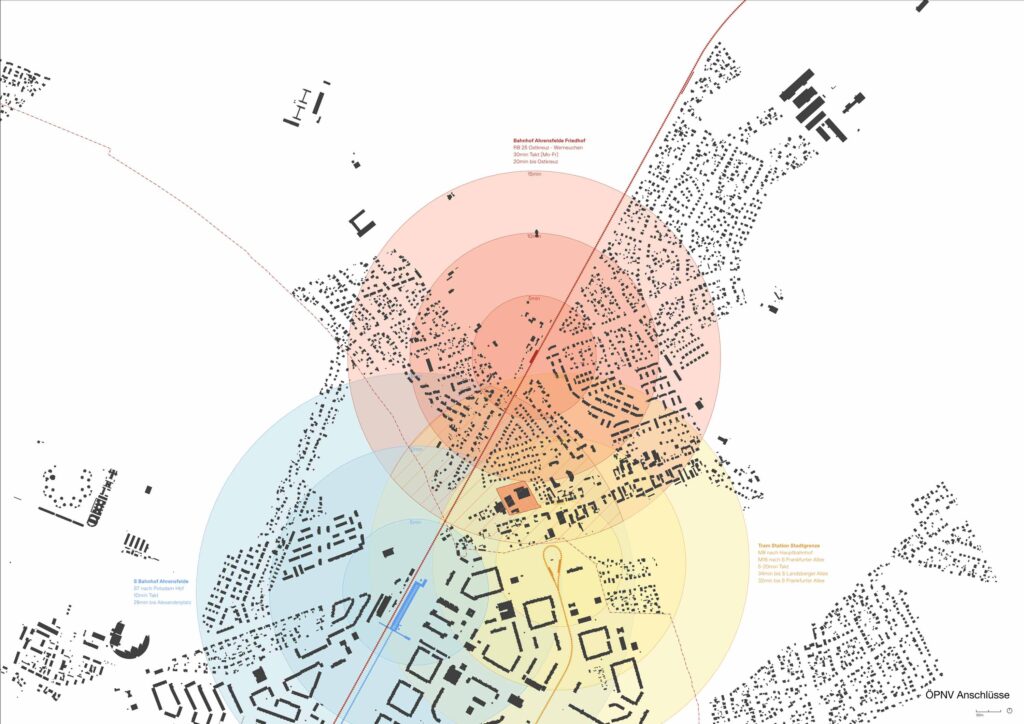

Current planning practices promote car dependency, and public space functions more as a transit zone than a place to linger.

> Yet Ahrensfelde is well-connected to public transportation—ideal conditions for a 15-minute city. A pedestrian- and cyclist-oriented design can help realize this vision.

The potential of underutilized land

Currently, highly standardized big-box architectures with parking lots arise to quickly fill programmatic gaps —urban design happens as an afterthought. This results in leftover spaces and further degrades the quality of public space.

> Specific, intentional planning can significantly enhance the spatial and social value of these areas and strengthen the potential of central locations as places of encounter and leisure.

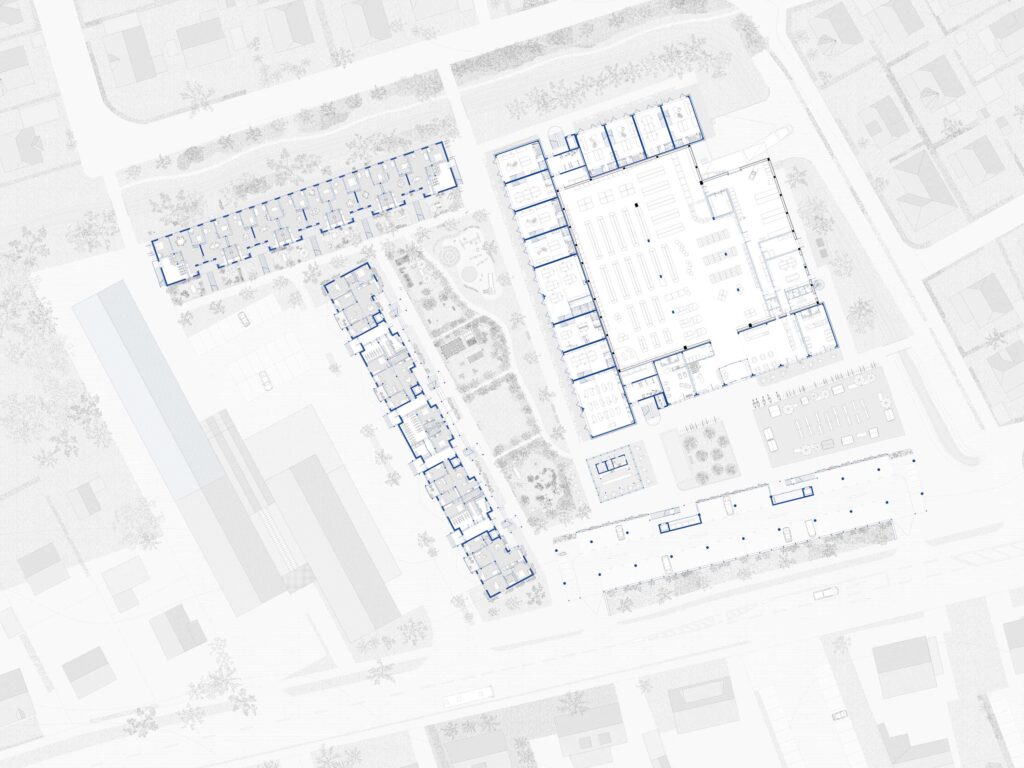

The project

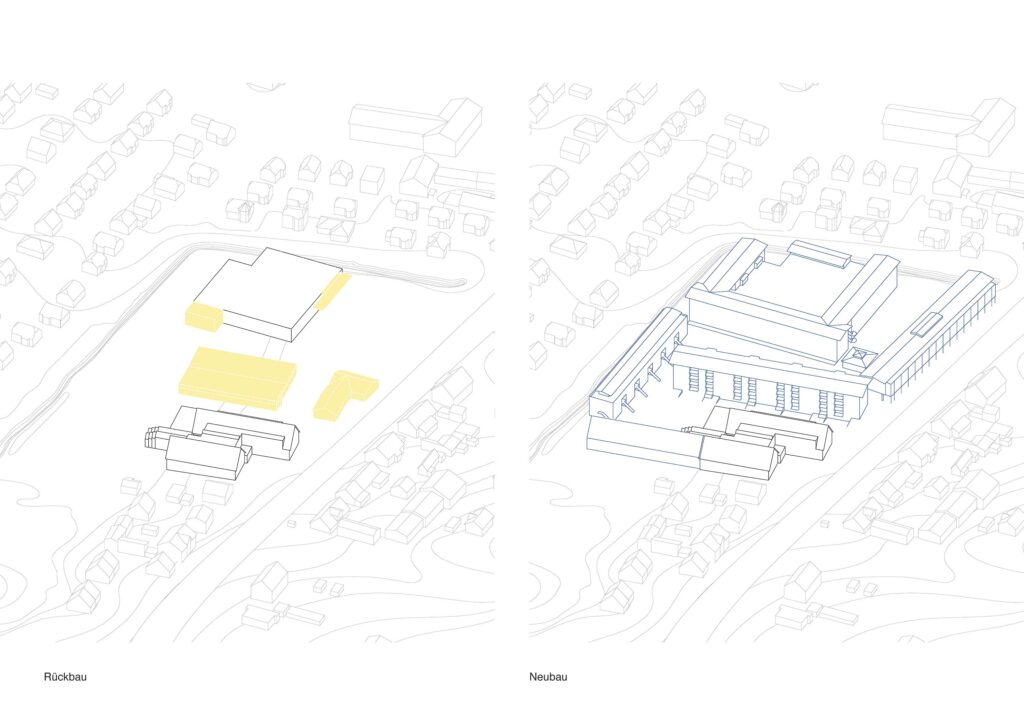

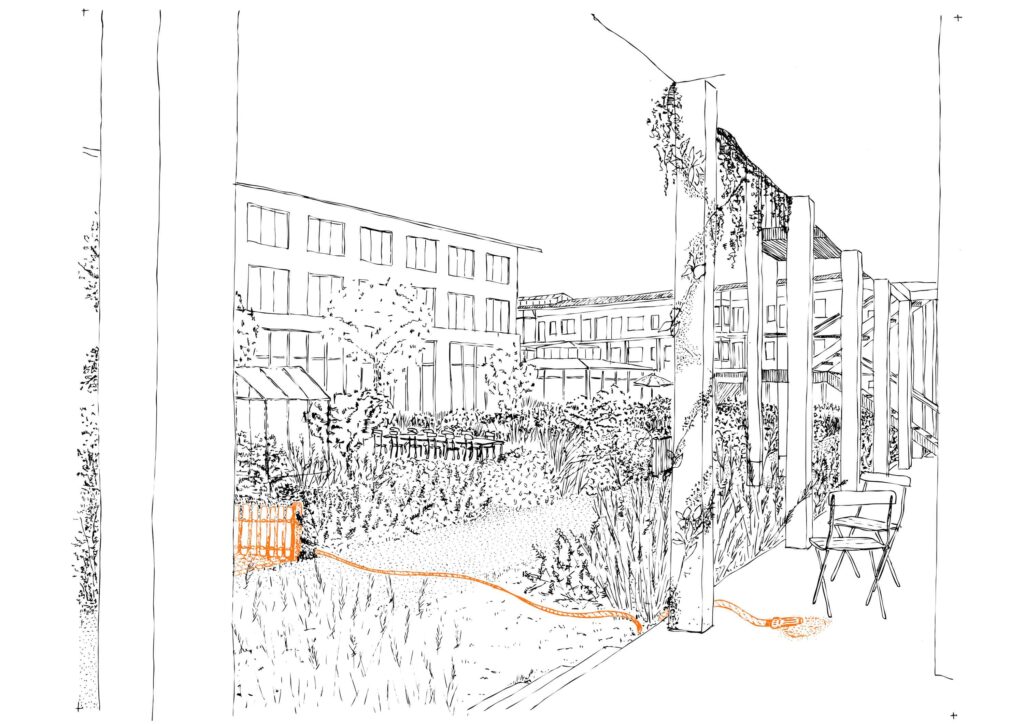

On a central site in town, near the Berlin city border, three elongated residential buildings and a redevelopment of an existing supermarket form a new ensemble. Three porous, programmatically distinct courtyards—Market Square, Residential Courtyard, and Rooftop Garden—structure the complex.

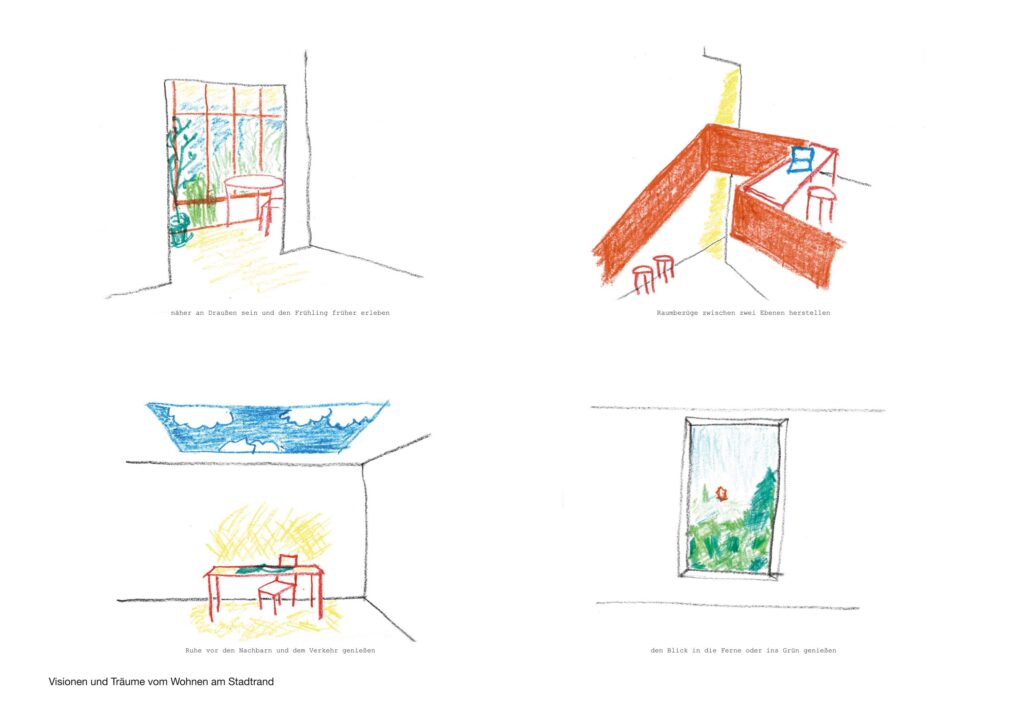

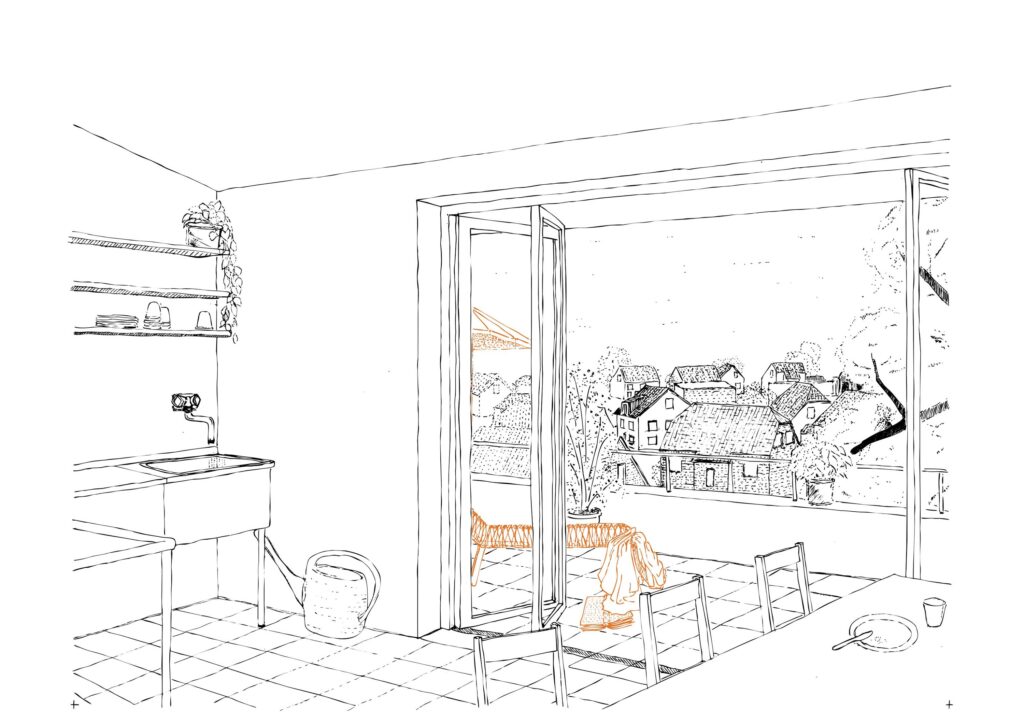

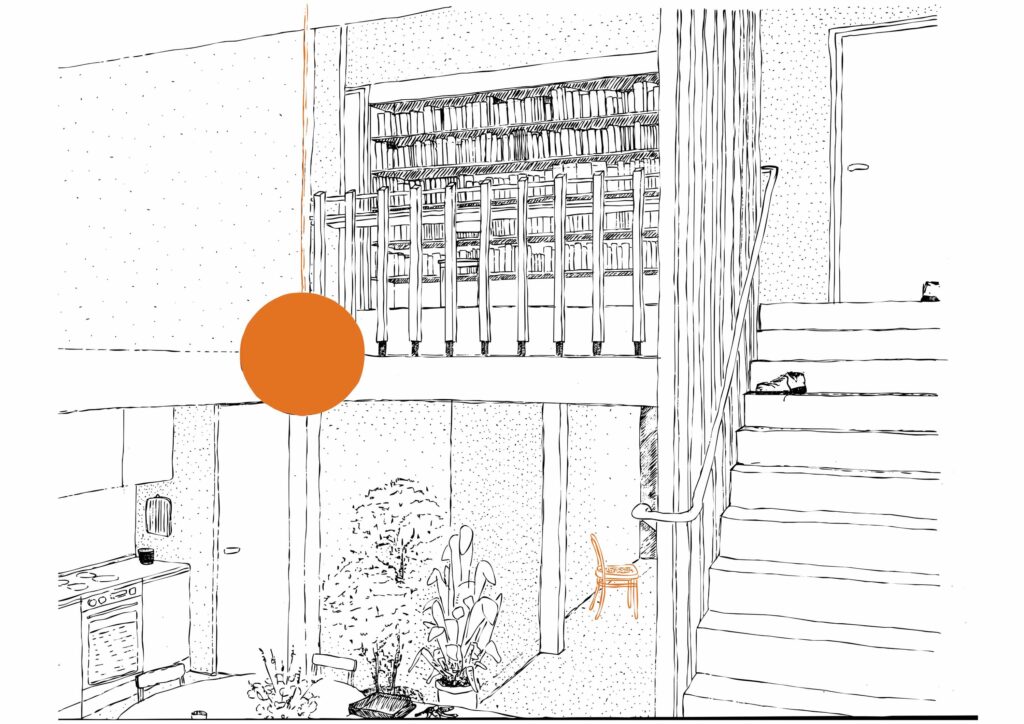

The four buildings vary in apartment size, circulation, orientation, site placement, and proportion of shared spaces. Nonetheless, all buildings embody defining qualities of living on the urban periphery: Each unit has a private outdoor space, is cross-exposed and more spacious than its urban counterpart, features naturally lit and ventilated bathrooms, and is accessed through open outdoor spaces. Flexible rooms that can function as studios, guest rooms, offices, or hobby spaces complement the apartments.

All buildings are designed in timber frame construction with load-bearing exterior walls and timber façades; only the base levels of the Winter Garden House and the Maisonette House are constructed using reinforced concrete, with the latter clad in lime sandstone.

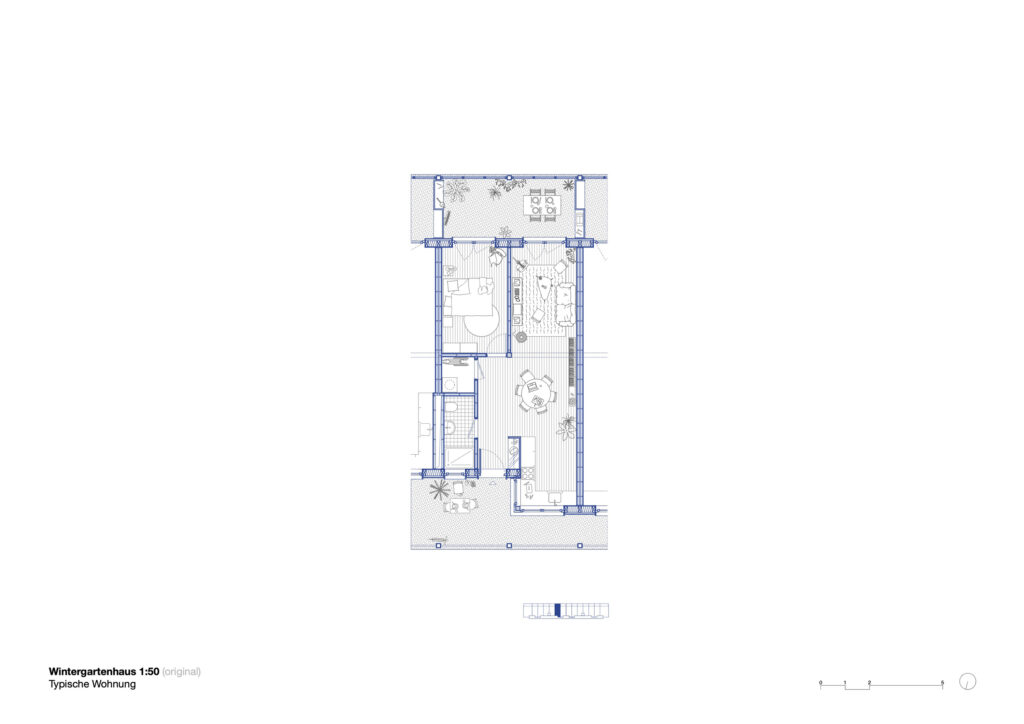

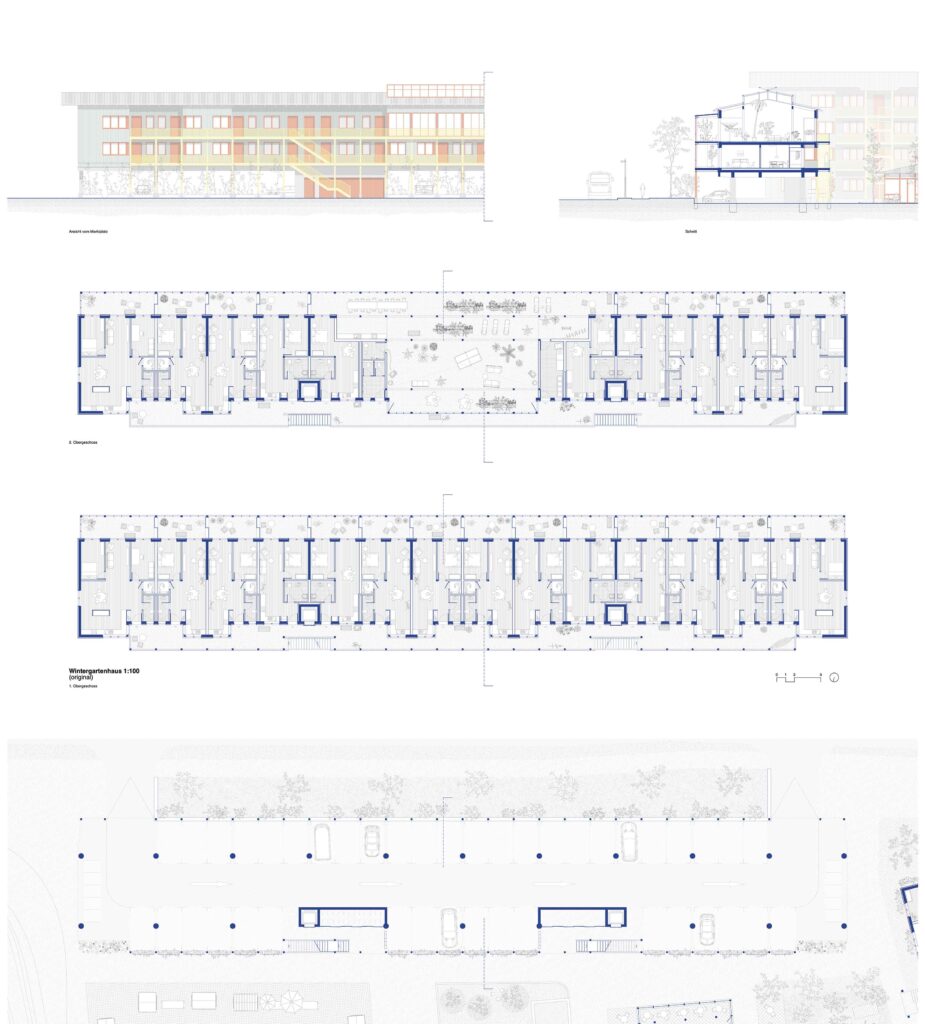

The Winter Garden House

Facing the village street, this building contains the smallest units, accessed via an external corridor. A private winter garden acts as a buffer against traffic noise and represents the most urban interpretation of a garden. Where the apartment sizes are smallest, the sense of community is strongest: residents share a large communal winter garden on the top floor, complete with a shared kitchen, laundry area, and two flexible-use units. The open ground floor serves as a parking area for supermarket customers during the day and residents at night. With a ceiling height of 3.5 meters, it can later be converted into retail units.

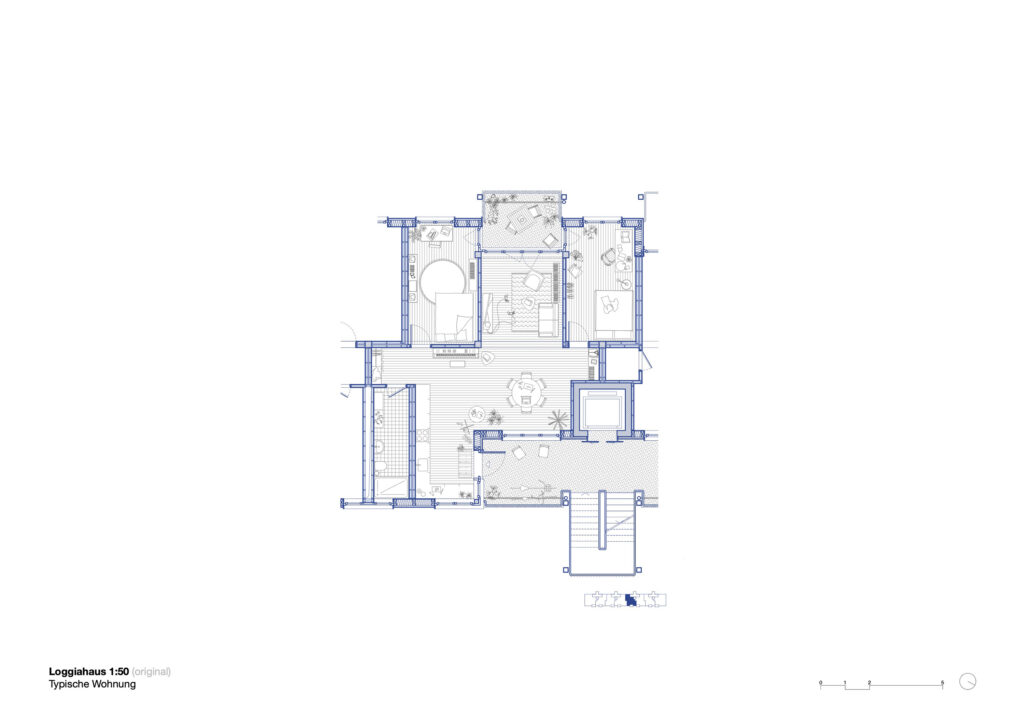

The Loggia House

Located by the Residential Courtyard, this building offers 3–4 room apartments, accessed via exposed staircases. Each unit has a covered private loggia and a semi-public outdoor space in front of the entrance, encouraging interaction with the immediate neighbors. Garden areas in the courtyard are shared by the units served by the same staircase. The plan provides basic infrastructure—water and electricity—but the design of these gardens is left to the residents. Parking is located in the basement.

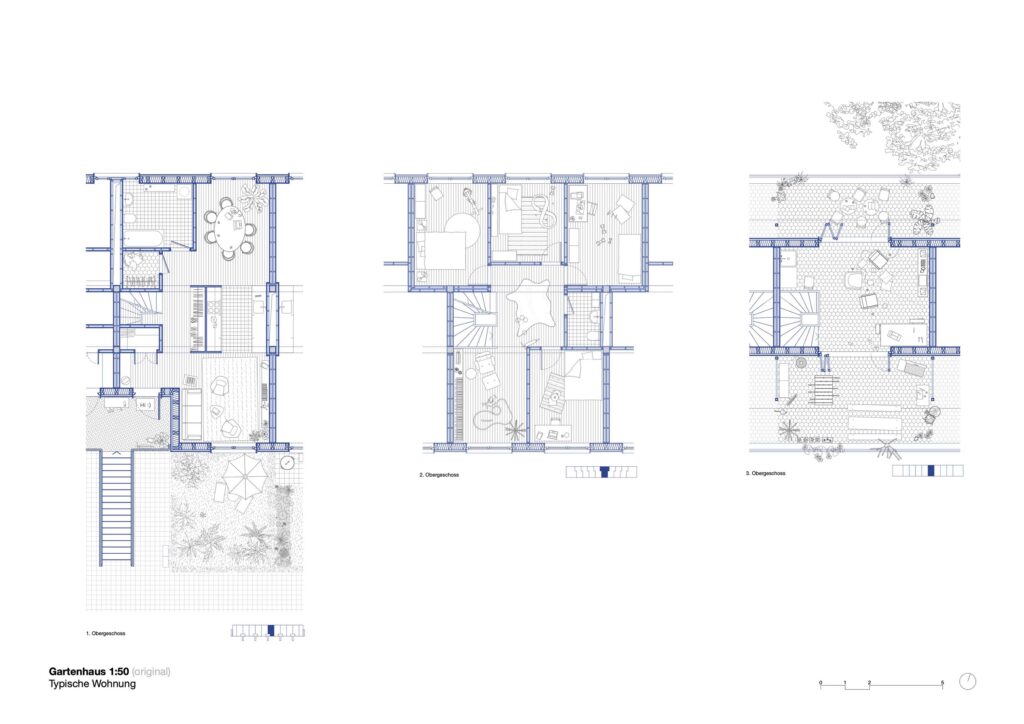

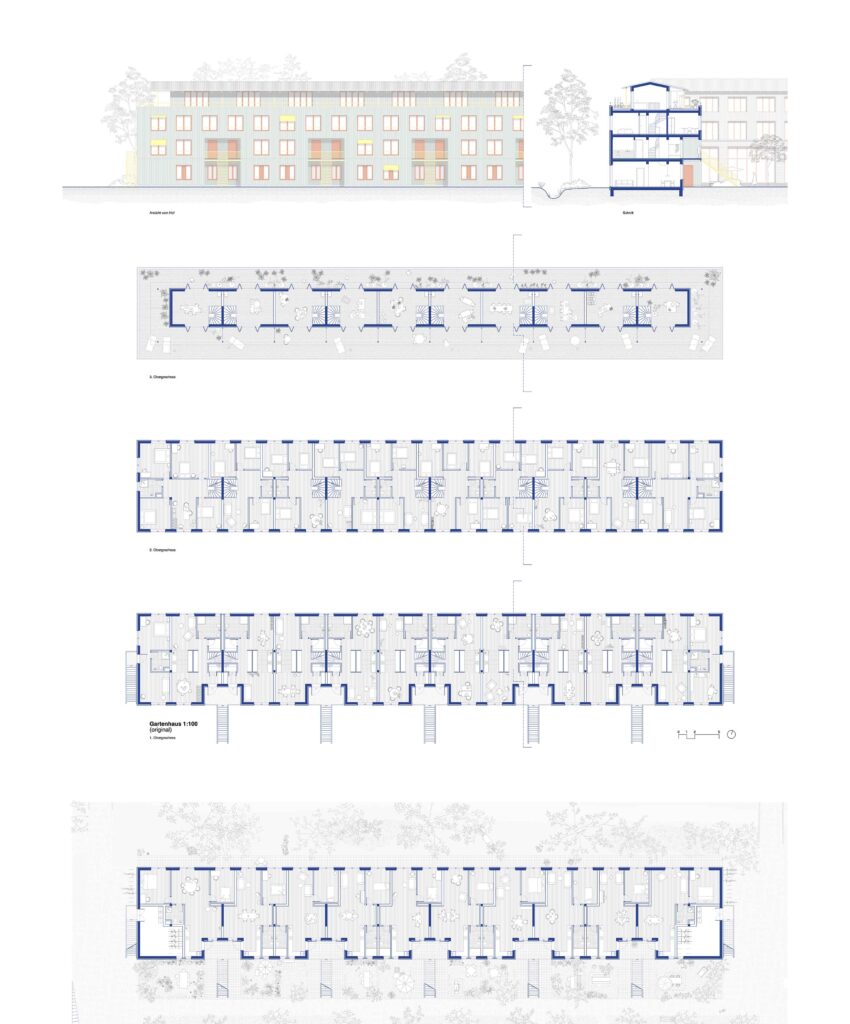

The Garden House

This house borders a green strip with a water channel and looks out toward a neighboring single-family housing area. Ground-floor units have direct garden access and consist of two rooms, while a three-story maisonette with a rooftop terrace sits above, nestled in the tree canopy. In terms of size, layout, and privacy, this dwelling comes closest to the character of a detached house.

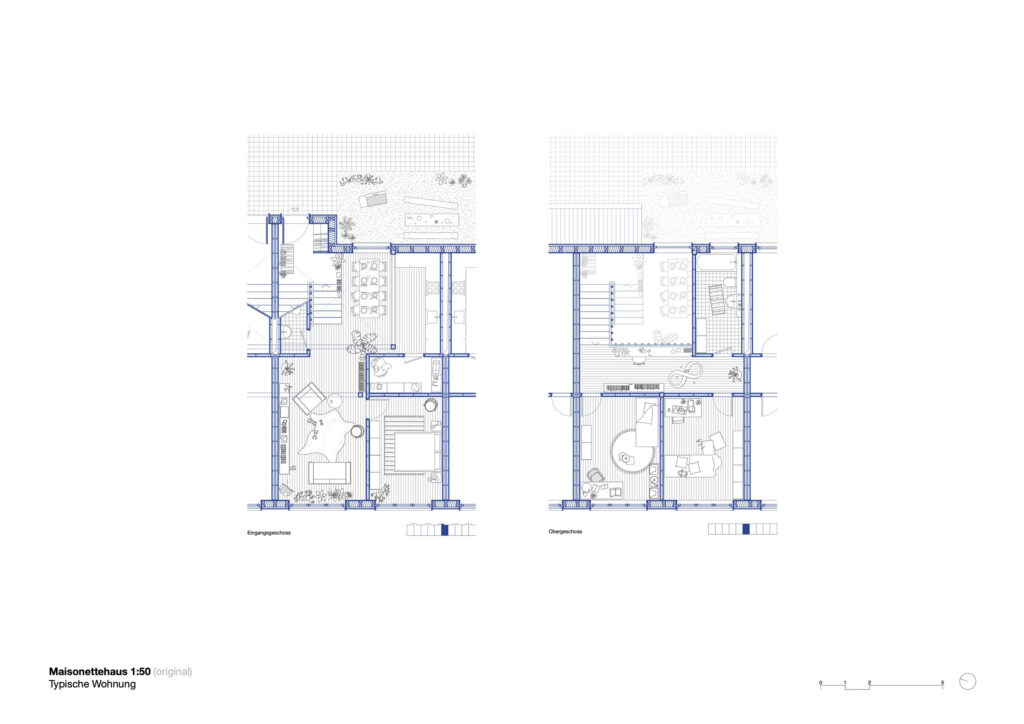

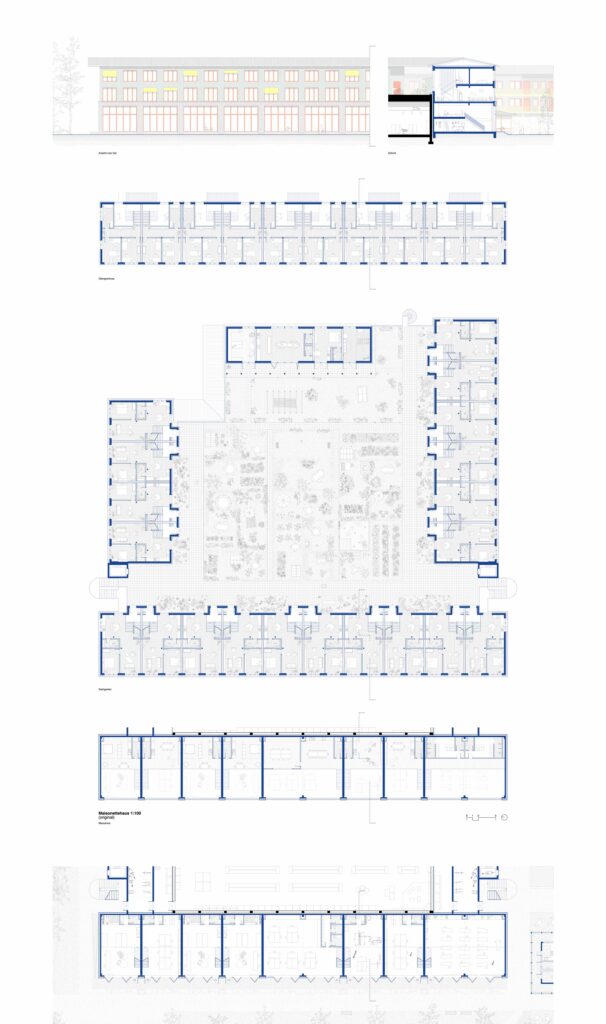

The Maisonette House

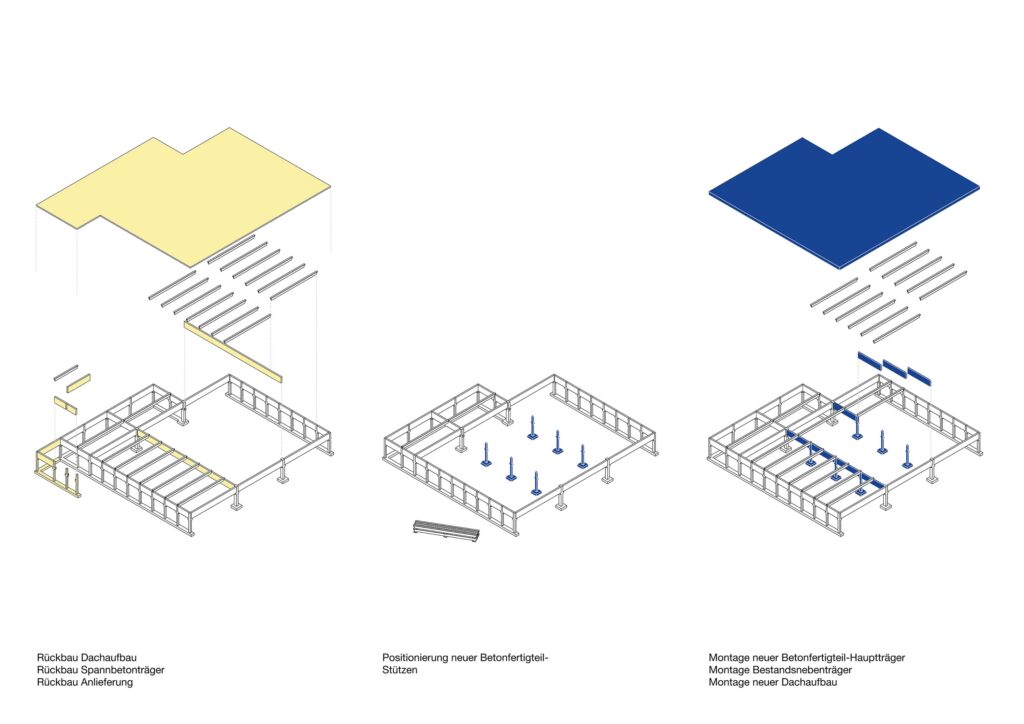

The ground floor of this building contains the supermarket entrance and additional retail spaces facing the Market Square. On the side of the courtyard and the green strip, flexible-use units with mezzanines and high glass façades offer ample light and can be used for commercial purposes, sports facilities, live/work studios, etc. The maisonette apartments above are accessed via the rooftop garden that sits on top of the supermarket and offer three-room units of medium size. They celebrate two-level living reminiscent of a detached house, while also offering immediate access to a private garden. A reinterpretation of the traditional allotment garden provides 30 garden plots for 20 units, to be distributed as needed, and includes a shared building for tools, events, and guests. This is made possible by structurally reinforcing and rebuilding the supermarket’s roof.

Name

Max Bilger

Year

2025

Type

Master Thesis